My week using Claude Code

I was very against using AI for any serious research code until recently. Then GPT-5 changed my mind a bit—it was genuinely good at writing complicated analysis and visualization code. For example, if I gave it a task that looked roughly like this:

- Given result dataframe, aggregate performance across multiple cutoffs and cluster first by A, then by B.

- Report bootstrapped performance.

- Make this efficient via multiprocessing.

- Visualize.

GPT-4 would fail already at step 1: it couldn’t produce correct grouping logic no matter how I prompted it, and then it made multiple mistakes in pandas and bootstrap code. GPT-5, on the other hand, completed the entire pipeline correctly in a single chat.

Still, I was somewhat unsatisfied. Its design choices were not really thought through, and it didn’t handle larger context or follow-up edits very well. It would get lost, introduce unnecessary abstraction, or gradually bloat the code. On top of that, copying multiple files and outputs back and forth was just tedious.

That’s why I turned to Codex CLI, but I was still unsatisfied with the quality, the UX, and how easily I hit the token limit. Honestly, the last part was the most frustrating. Then my friend kindly offered his Claude Max account 2 weeks ago, and it completely changed my research workflow.

Features I liked

For my research, I usually start from a large codebase—like OpenFold or Genie—and either (i) implement a new feature or (ii) prototype a new research idea. Feature work is more straightforward and closer to standard SWE tasks: adding a new dataset, writing tests, or implementing a metric/benchmark. It’s somewhat expected (or is it?) that AI performs well on these well-defined problems—but there were still a few things about Claude Code that I really liked.

1. Plan Mode

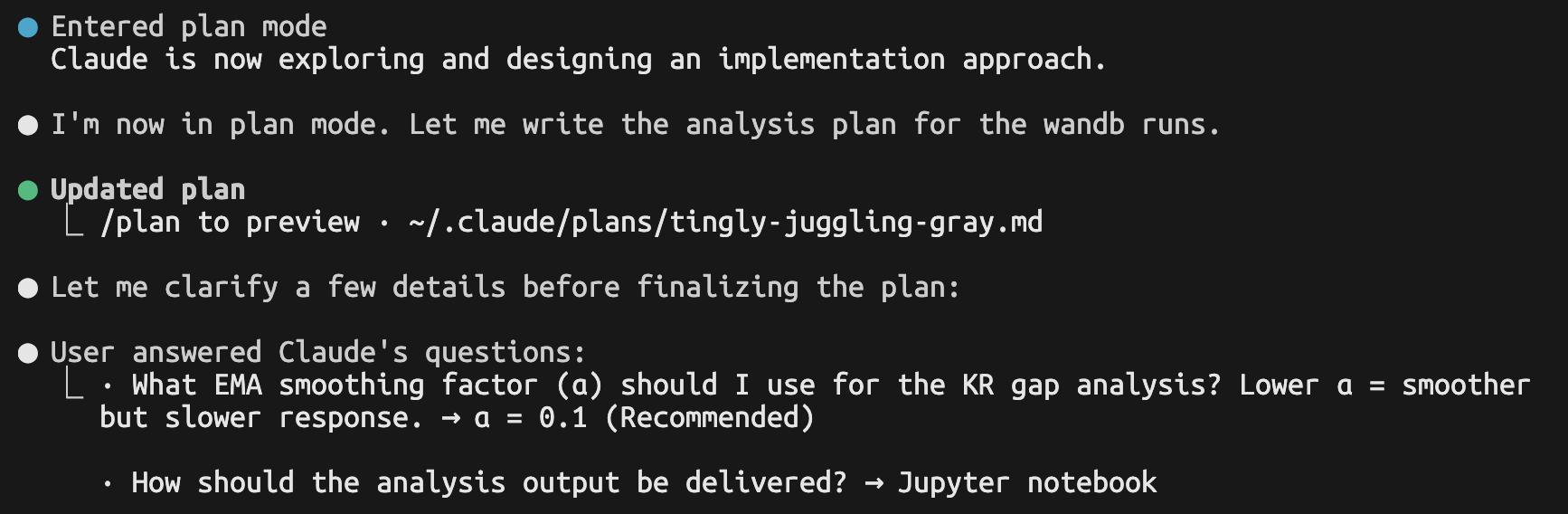

As advised by my friend, I prompt with “Plan. ultrathink” at the end, which triggers Claude to make a plan in its highest thinking mode. This Plan mode is great because you can review whether Claude’s understanding and approach are correct before it commits to a full-blown implementation.

2. Collaborative coding

If I change things, Claude Code understands my intent and sticks to it. This feels very different from ChatGPT, which often anchors itself to its first version of the code, even after I send updated snippets in follow-up messages. ChatGPT may forget that I renamed variables or corrected its misunderstanding; Claude Code doesn’t.

I don’t know exactly how Claude Code is trained under the hood, but it’s clearly designed to be collaborative—it assumes the user will freely modify the code and adapts accordingly.

3. Execute–debug loop

Claude Code is also very good at debugging through iterative execution. It works best when explicitly asked to write and run tests, but even without that, it still reasons through output. For example, when experiment logs weren’t loading correctly from Weights & Biases, it added three different approaches and asked me to paste the notebook output. (If it wasn’t a Jupyter notebook, it would run the code itself, check stdout, and pick the right one.)

# Method 1: history() h1 = test_run.history(pandas=True) # Method 2: history with samples h2 = test_run.history(pandas=True, samples=5000) # Method 3: scan_history (iterate first 5 records) scan_records = [] for i, record in enumerate(test_run.scan_history()): if i >= 5: break scan_records.append(record)I’ve updated cell-4 with extensive debugging to test all the different WandB API methods. Run it and share what you see.

How this changes my research workflow

Previously my workflow (given a clear goal/idea, how do I make it work?) looked like:

- Think of a good idea

- Implement the idea

- Write code to run experiments

- Write code to analyze results

- Look at the results → go back to 1

Time-wise, 2–4 usually dominates, especially when the project is in execution mode rather than planning/ideation. AI lets me spend more time on 1 and 5, where the actual research thinking happens. Let me give an example of how steps 2–4 are significantly reduced.

Recently I wanted to check the effect of my method, but I had 6 different benchmarks, my method was still sensitive to two hyperparameters, and I had two candidate architectures. So I asked Claude to implement the architectures and make them configurable (step 2), then write a sweep script (step 3). A few hours later, everything ran and logged to WandB, and I had Claude generate the analysis script (step 4). I prompted it to:

I ran bulk experiments of

@train.pyusing the Slurm script@sweep.sh. Now I want to load WandB runs to analyze results. A few things I’m interested in:

- Which configuration maximizes the KR gap? Use EMA smoothing and define a threshold (e.g., >50 consecutive steps where KR gap > 0.1).

- Which configuration decreases

val/mean_min_rmsdor increasesval/mean_best_tm? Results at step 0 give baseline performance.- For those successful configurations, how do other metrics behave (KR gap,

div_pairwise_js, etc.)?Plan. ultrathink

Writing all this analysis myself would easily take two hours. Now, I mostly read Claude’s analysis and spend my time thinking about the next step. Also, by driving the cost of “write code to analyze results” close to zero, my analysis actually became more rigorous. Obviously I can’t manually inspect hundreds of WandB runs. Instead of relying on one-off runs or intuition, I can ask Claude to analyze any small question that comes up in my mind, and get concrete results (visuals, significance tests, everything!) almost immediately.

Takeaways

How to use the system is explained well in this Anthropic blog post. But here’s my takeaway: don’t expect it to do things that would be hard even for you. I think this mindset really matters when using an AI agent for research code. It won’t synthesize real research insights, and it definitely won’t answer my research questions. Most of the time, it’s just doing what I could do myself, but would take a few hours. The ideas, insights, and judgment still have to come from me. Whenever I got lazy and asked it to solve my research problems (e.g., “design a better adapter architecture that does XYZ” or “propose a regularizer that fixes XYZ”), it never gave me a good idea. Which makes sense.

“Hard for me” is a pretty low bar (haha). Anything that makes me think for more than a minute, scribble on paper, or look up research papers already counts as hard. Here’s an example: I was writing tests for a DockQ metric implementation, which involves aggregating across molecule types and applying different masks. Claude suggested too simple unit tests like dockq(a, a) = 1, even though I prompted it to:

Please create realistic scenarios consisting of real coordinate values and compare against exact value. Don’t define tests that is not exact, e.g., random coordinates or degrade the structure and check dockq decreases.

What I wanted was deliberately design coordinates and check exact RMSD values, where the value should be wrong if masking or summarizing code is wrong. Then I realized: it’s pretty hard to come up immediately with those scenarios since RMSD involves optimal alignment. I should maybe draw some coordinates and think through right cases.

Same for the scenario above.

- Which configuration maximizes the KR gap? Use EMA smoothing and define a threshold (e.g., >50 consecutive steps where KR gap > 0.1).

I’m pretty sure if I had not elaborated on EMA smoothing and consecutive steps criterion, it would have taken a lot of back-and-forth to clarify what I meant by “maximize”.

I think it’s important to reduce ambiguity in the hard parts. In the end, I want AI to do the boring work (even though I love coding haha)—so I can do the thinking.